Alexander McQueen

Fashion as a massacre

This march, it was twenty-five years ago, that a young alexander Mc Queen – just a few days shy of his twenty-sixth birthday – presented his Highland Rape collection at London Fashion week in a défilé that would instantly catapult him to the zenith of fashion superstardom.

McQueen, later seen by many as a long-desired savior of British fashion was an unlikely candidate for the job. In her book God and Kings, which examines the rise and fall of McQueen and his contemporary John Galliano, journalist Dana Thomas writes: “He was gruff. He maintained his Cockney accent riddled with profanity. He shaved his hair into a Mohawk, had tattoos before they were fashionable, dressed in faded T-shirts and tatty jeans, and was missing a front tooth. The British fashion establishment did not like him, and quietly wished he would just disappear”.

Answering questions after a recent lecture on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of McQueen’s untimely death, I realized with some bewilderment that the young students who had so eagerly been listening thought of McQueen not as a man, a rebel or a genius of fashion – but as a certain type of footwear, a white sneaker of all things.

The oversized, raised-sole model, whose minimalist approach is offset only by a colored patch at the heel, was launched in 2016 and recently named the most sought-after shoe of 2019 by the the e-commerce platform Lyst. German trend analyst Carl Tillessen explaines the popularity of the shoe as a result of its demure aesthetics: “It’s a dad sneaker, but not an ugly sneaker.” And an article in Cosmopolitan praised the “versatility and comfortability” of the shoes – two qualities most certainly not associated with McQueen during his lifetime.

In many ways, it serves as a poignant analogy of how the fashion industry lost its bite in the last decade, replacing the prickly radicalism that lay at the core of McQueen’s work with the blandest of products – a move that is as culturally devastating as it is commercially successful.

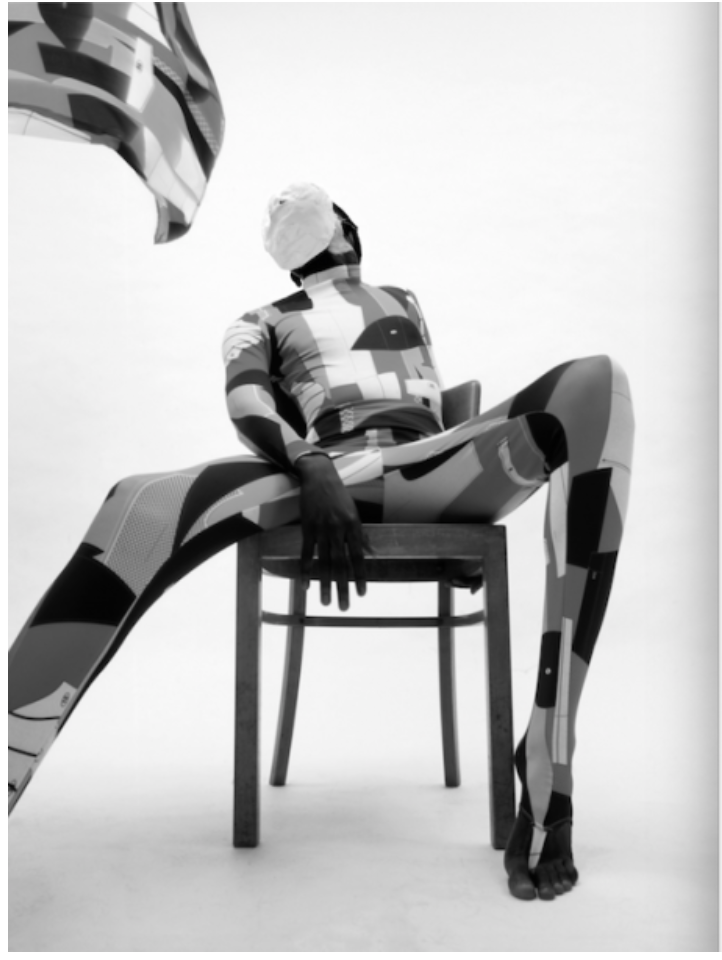

Back in 1995, with his career still ahead of him, McQueen’s plans where distinctly different. Just minutes before the opening of Highland Raped he made crude modifications to the clothes: “There were all these beautiful blue lace dresses and he was hacking at them with his shears”, his mother Joyce, who was backstage in the packed tent, remembers “And I was Crying ‘No, don’t spoil them’”. The effect of the models stumbling out in torn lace, wearing opaque blood-shot lenses and dishevelled hair was stunning and frightening at the same time. With the spectacular show, McQueen expressed his deep-felt conviction that beauty was violent, grace was painful and that fashion was a massacre.

Raised working-class, he felt the subtle yet powerful restrictions stronger, than many of his more privileged fellow studends at London’s renowned Central Saint Marin’s College – as a result he fought the system harder than them. He had started his career as a humble apprentice on London’s famous Savile Row. He knew the codes of the upper classes were not flamboyant and obvious but hidden in the details easily overlooked by the untrained eye: the luster and fall of the fabric, the precision of the cut, the intricacy of the tailoring.

Like Vivienne Westwood, McQueen loved the complicated garments of 19th Century bourgeois culture, often incorporating high collars, bustles and crinolines into his dresses, only to thwart them with a punk attitude, a gesture of refusal.

Writer Dana Thomas refers to the 19th Century as the “golden age of luxury” when consumers knew that being able to pay more money meant getting something truly exceptional in return. Up until the early 20th Century traditional luxury items like dresses from Christian Dior, luggage from Louis Vuitton or jewelry from Cartier carried prestige because of their superior craftsmanship, outstanding quality of material and design. Thomas describes today’s luxury business as a sham, because contemporary products are lacking any equivalent value – their exorbitant price tags instead being backed only by symbolic values.

This is especially obvious in the sneaker market, that shamelessly seeks to upgrades shoddily produced items made of inferior materials by associating them with celebrity and creating artificial scarcity. From an aesthetical as well as a political perspective, McQueen’s best-selling product of 2019 could not be further from his iconic Armadillo boot, that debuted in Spring/Summer of 2010. Even though the shoes, along with his famous Knuckleduster handbag, became prestigious and easily recognizable symbols for his emerging brand, they were never just products in a one-dimensional sense. They were parodies of products and at the same time, they were works of art. Wearing them required not just money, but passion, dedication and the courage to look ridiculous, even ugly in the eyes of many. Because ultimately, that was how McQueen himself felt during his too-short career in the world of luxury goods and high glamour: incongruous, displaced and angry.

One cannot fail to see, that the very reasons the British establishment loathed Lee, as he was known to his friends, where the same that inspired the unbridled admiration of his many admirers and supporters. Iconic fashion stylist and eccentric Isabella Blow who famously bought his entire graduation collection from Central St. Martin’s for £5,000. The young designer and his patron shared a complicated relationship. The American socialite known as BillyBoy, and trusted friend of McQueen, remarked: “At times, Lee he could be dismissive of Issie and make fun of her. He treated her very badly, and at times it was so gross I thought: ‘How can he say that?’ But there was a sort of psycho-sexual relationship between the two of them. She was completely enamoured of him and his work, and I think he wanted to punish her. There was something deeply masochistic in his personality: I think by punishing her, he punished himself.”

Putting up a show like Highland Rape would be impossible in 2020 – not just because of the sensitivities surrounding the depiction of sexuality and violence in the post-#metoo era. Fashion shows are different affairs these days, trend forecaster Li Edelkoort famously ranted in 2015: „Fashion shows are becoming ridiculous; 12 minutes long. 45 minutes driving, 25 minutes waiting. Nobody watches them anymore. The editors are just on their phones; nobody gets carried away by it. It’s a ridiculous and pathetic parody of what it has been.”

In today’s globalized and accelerated digital culture the spectacle of fashion was downscaled to fit the confined space of a smart phone screen. The finesse of a silhouettes, the brutality of the slashed materials, the stilted walks and blank stares of the models would all be lost in the process. In order to stand up to a highly competitive market, yearning for a constant stream of new offerings, a brand needs products that don’t overextends the critical abilities of its consumers.

Just one year after Lee’s passing, the Duchess of Cambridge to-be, caused a stir when announcing McQueen – or rather the brand’s new creative director Sara Burton would be making her wedding dress. Many believed that Vivienne Westwood, who had recently earned the award for British Designer of the Year would have been the obvious choice. After all, McQueen’s bloodied lace and tartan dresses, symbolizing the rape of Scotland by the British seemed hardly a fitting theme for the fairytale wedding the already weakened royal family was so desperately looking forward to. In the end, it worked out to everybody’s advance: while Westwood publicly sneered at Middleton, calling her style “ordinary”, Burton complied to the royal wished and created a dream dress of innocent lace – that was neither torn nor sullied.

Lee’s story really ends here. Admired by many, understood by few. Let’s hope generations to come will forever associate his name with rare creations stubborn beauty – not the crowd-pleasing banality of a white sneaker.

-Published in Numéro Berlin 8/2020